Mi Historia

The story I carry in my bones

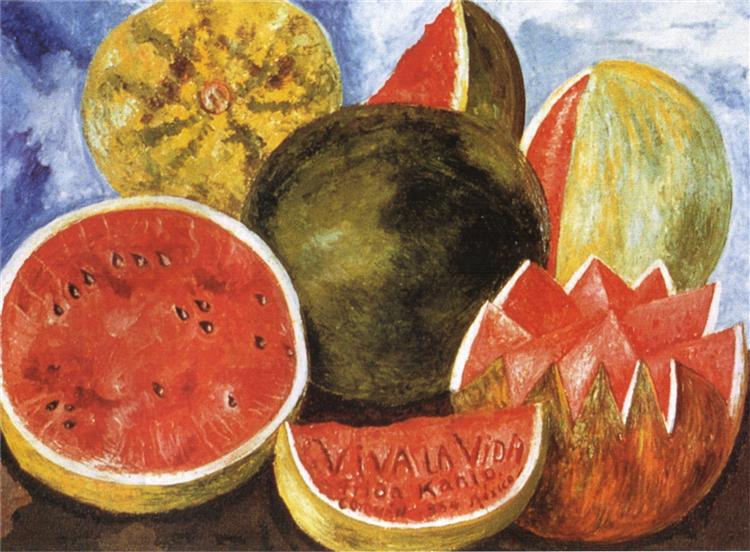

They say I was born in 1907, but I preferred to claim 1910 — the year of the Mexican Revolution — because I was a daughter of that upheaval, that rupture, that insistence on becoming something new. I came into this world in La Casa Azul, the Blue House in Coyoacán, and I left it from the same bed. Everything I was happened between those blue walls.

My father, Guillermo, was a German-Hungarian photographer who taught me to see the world through lenses and microscopes. He showed me how to look at things with such precision that you could find the extraordinary hiding inside the ordinary. My mother, Matilde, was devout and fierce in her own way. From her I learned that love could be both shelter and cage.

At six, polio seized my right leg and made it thin and short. The children called me Frida pata de palo — Frida peg-leg. I learned to hide it with long skirts. I learned something more important: that the body is a battlefield, and I would be a warrior, not a victim.

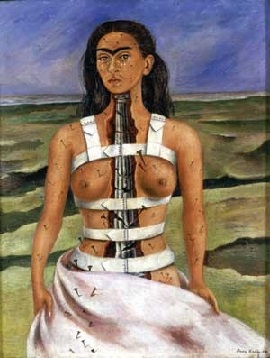

Then came September 17, 1925. I was eighteen. A streetcar collided with the wooden bus I was riding. An iron handrail pierced me through the pelvis. My spinal column broke. My collarbone broke. My ribs broke. My right leg broke in eleven places. My right foot was crushed. They did not expect me to survive. But I did — I always did — though survival is not the same as being whole.

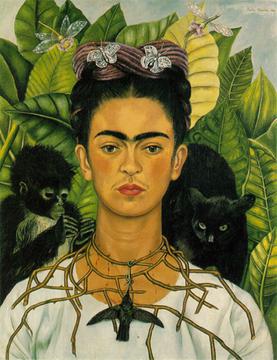

It was in that bed of recovery, encased in a plaster corset, that I began to paint. My mother hung a mirror above my bed and built me an easel I could use lying down. And so I painted what I could see: myself. Not out of vanity — out of necessity. I was the only model who would hold still long enough.

I never studied painting to be an artist. I painted because I had no other way to speak about what was happening inside me. Every painting was a scream made beautiful, a wound made visible, a truth that had no other language.